George Hawkins – a true story from the Caen Hill flight

The story of George Hawkins from the Caen Hill flight. Murder, accident, or suicide? What do you think?

George Hawkins was born in Melksham and married Elizabeth Ada Douse in 1872. They had eight children, five boys and three girls. From the 1870s until the early 1890s the family lived at 42-43 Northgate in Devizes, where George ran a registered slaughter house and butcher’s shop. By 1890 he was advertising the business to let.

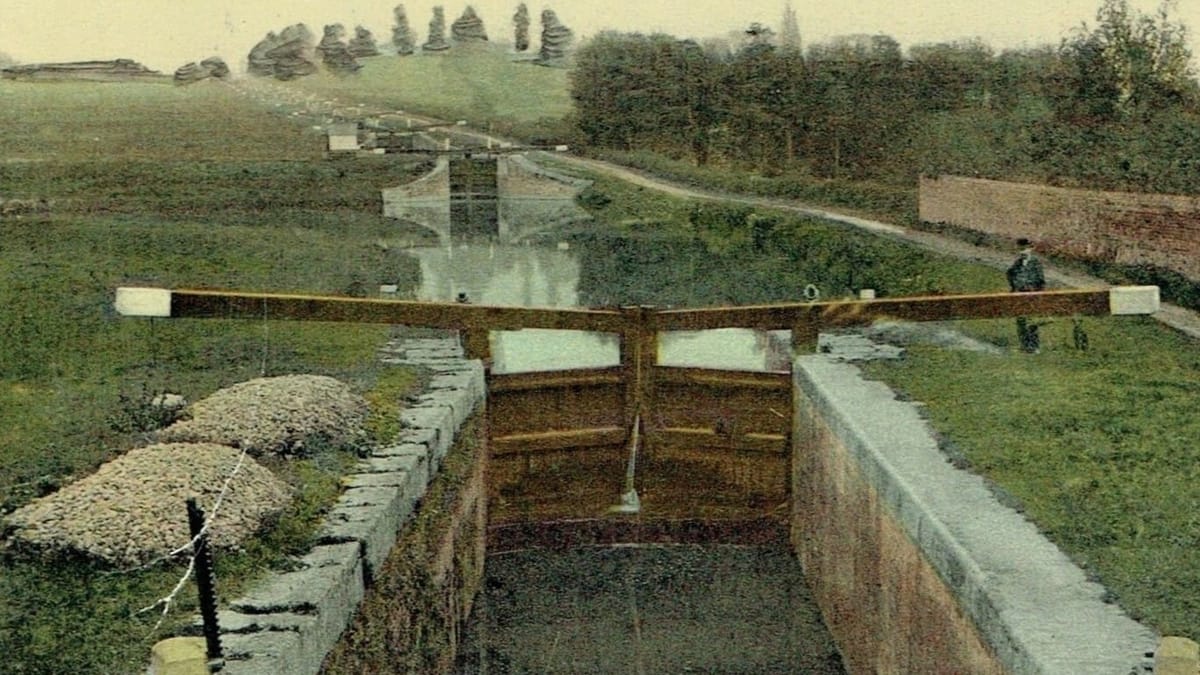

George moved to Highfield, Caen Hill, some time between 1891 and 1894 and here he became well known as a farmer and dairyman. The earliest record I have found showing the family at Caen Hill is 1894 when his daughter Grace was Christened. Although today we know Caen Hill best as the name of the lock flight, it is also the name of the road running parallel to the canal.

Despite checking on a number of old maps I have been unable to positively identify George’s house. The families recorded on the 1911 census on either side of Highfield were Hazlecroft and Sunnyside Farm, so Highfield may have been a property on the north side of Bath Road on the site of Caen Hill Gardens, which was built from 1924 onwards. In 1905 George’s address is recorded on his son Albert’s enlistment form as Caen Hill Farm, so Highfield may have been the farmhouse or a cottage at Caen Hill Farm (previously named Woodbine Farm).

On Saturday, September 16th 1911 George drowned in the Kennet and Avon Canal, age 64 years. At the inquest the Coroner and jury attempted to establish whether his death was an accident or a suicide. Before the Suicide Act 1961, committing suicide was both a legal offence and a religious sin, and anyone who attempted and failed could be prosecuted and imprisoned. In certain circumstances the families of those who succeeded could also be prosecuted. It is understandable that George’s family would go to great lengths to prove that his death was an accident. But was it really a suicide, and were his family complicit in it?

The Wiltshire Times reported that in about 1909, George attempted to commit suicide by cutting his own throat, and was bound over to the care of his adult sons. He appeared to recover from this incident, but occasionally complained of severe pains in his head.

The 1911 census was taken five months before his death. At that time two of his sons, Harry, age 26, and Arthur James, age 20, were still living at home and helping on the farm.

According to his youngest son, Arthur James Hawkins, George had been suffering from giddiness and fainting fits for some months, and had fallen in the fields on a couple of occasions. Nevertheless, he had not seen the doctor for over twelve months before his death. Arthur said that he had seen George stagger and fall the previous Tuesday (or perhaps Thursday, the newsprint is somewhat illegible) but his father came round in about five minutes. He went indoors and seemed all right afterwards. George intended to visit the doctor during the week, but put it off.

On Saturday morning George had complained to Arthur of giddiness, but had made breakfast, carried on with business as usual, and had sold some pigs. After this Arthur took his father in a pony and trap and dropped him off in the street near Dr McKay’s. George collected a bottle of medicine, which was later found in his pocket. Dr McKay did not fully investigate George’s symptoms and could throw no light on the matter.

George told his son to drive back to the farm and get on with his work; he himself would walk back slowly on foot. When Arthur left him at 10 o’clock, he had seemed “alright”.

The shortest way home was via the towpath. A report before the inquest claimed that witnesses saw George in the street, and a few minutes later a girl walking along the towpath noticed his body in the canal near the Bathing Place, and raised the alarm. The inquest report does not mention a girl, however. Evidence was given by George Henry Redsall, a miner from Poulshott on a visit to Devizes. He saw something which looked like a small white spot floating under the surface of the water in the centre of the canal. Soon afterwards he realised that he could see clothing, at which point he raised the alarm. The Bathing Place attendant Mr Wiltshire, along with Superintendant Buchanan, Superintendant Hillier, and others from the Central Police Station, were soon on the spot.

Superintendant Hillier described how he too could see a white spot. It soon became apparent that this was the bald patch on George’s head. Then the sun broke out, and the men could see his hands. Mr Wiltshire waded into the canal and dragged the body to the bank. George’s body was taken from the water and Superintendant Hillier attempted artificial respiration, but to no avail.

George’s pockets contained 10 shillings in gold, 5s. 6d. in silver, and 51/2d in copper, a bank and cheque book, a pipe, some tobacco and the bottle of medicine. There was no letter. His walking stick was found on the bank nearby.

George’s body was taken the the Central Police Station to await the inquest. Dr Trow examined the body and declared the cause of death to be aphyxsia from drowning. There was no evidence of injury.

The inquest was held on Monday September 18th at the Central Police Station in Devizes, under Coroner G.S.A. Waylen. The Coroner questioned Arthur intently about his father’s state of health, in particular his giddiness, and asked whether George had ever tried to do away with himself. At first Arthur denied it, then admitted that his father had tried to cut his throat. Arthur denied that his father was depressed or worried about his giddiness, or that he had money worries, although his wife had been seriously ill.

George’s sister in law confirmed that she had seen George fall a few weeks before his death, but she insisted that he had not seemed depressed. George’s second son, Alfred John Hawkins, said he had seen his father last on Friday evening, and he had complained of being rather dizzy.

The Coroner continued his questioning to establish whether George might have been sufficiently depressed to do away with himself. A juryman chimed in, saying George had recently lost a cow but had not been worried about it. A juryman (perhaps the same one) said he had had a chat with George on the morning of his death and that he had seemed “quite as usual”.

The Coroner concluded that given the lack of evidence to indicate suicide and it was likely that he had fainted and fallen in the canal. The Jury returned a verdict of “Found Drowned”.

The Great Western Railway’s 1911 Accident Register lists George’s death, referring to him as a 'trespasser', and states that he was found drowned in the canal on Saturday September 16th 1911.

George’s widow Elizabeth Ada Hawkins died at Highfield, Caen Hill, on July 12th 1913, after a long illness.

Sources:

Genealogical Research

Western Daily Press Monday September 18th 1911.

Wiltshire Times Saturday September 23rd 1911.