A Twist in the Tale on the Grand Union Canal

Was it suicide or was it murder? Early on the morning in July 1880, a pair of horse boats loaded with chalk left Stoke Hammond lock...

Early on the morning of Monday 19th July 1880, a pair of horse boats loaded with chalk left Stoke Hammond lock, where they had been stopping over since Sunday. On the first boat were eighteen year old George Masey, one of Birch’s employees, who was driving the horse, and another employee, John Twist, who was steering. I believe that John Twist was born in Birmingham in 1858, the son of John Twist, a button burnisher, and Harriet nee Billins.

On the second boat was the master of the pair, John Birch, who was born in Stoke Prior in about 1818. He married Matilda Yeates in Stoke Prior in 1845, and they had many children, most of whom were born on boats and died in infancy. In 1875 Matilda died, so John was left to care for the two youngest children, Emily 10, and a son, William, who was 8 years old. On this journey, a daughter was driving the horse, and a son was steering. It seems likely that these were Emily and William, as John’s two elder surviving daughters, Betsy Ann, who was about 30 and Jane, about 28, were both married, and were probably with their husbands.

They proceeded north up the Grand Union Canal. At Fenny Stratford they stopped, so that the crews could eat their breakfast on board. George Massey and and John Twist swapped places for a while so John could walk and George could steer. At the next bridge they swapped back. John was now steering again.

At about 7.30am the boats reached Woughton Bridge near Woughton on the Green, where John called to George to get back on the boat as he wanted to go over the hedge. (I suppose that was a euphemism). John jumped off the boat onto the towpath, and stood against the wall of the bridge as the boat continued onwards. George did not witness John going over the hedge, but he fully expected John to rejoin the boat at the next bridge.

As the second boat drew level with John, he called out to his employer.

“Gaffer, I shall leave you here.”

“Very well, you had better come and take the two or three ha’pence due to you,” Birch replied.

“Never mind the ha’pence,” said Twist, “I shall not go any farther with you.”

The boats continued on their way, leaving Twist still standing against the wall of the bridge. After about five minutes, Birch’s son, who was steering the second boat, called out to his father,

“Father, Twist has jumped into the bridge hole.”

Birch looked back, but could not see Twist. George heard the shout and looked back, but he couldn’t see John either. He couldn’t get off the boat straight away as the water at the side of the canal was not deep enough. They went on to the next bridge, 18 chains further on, where they stopped. Birch grabbed his boat hook and walked back with Massey to the spot where Twist had jumped into the water. Ten more minutes had passed by the time they got there. There was nothing on the bank belonging to John Twist, and there was no sign of John in the water.

Birch began dragging the canal with his boat hook, while Massey went in search of a policeman. After about fifteen minutes Twist’s body was recovered, a short distance from the bridge, and Birch pulled it out on to the bank. John Twist was dead, and there was nothing anyone could do for him.

Now here’s the twist. John’s legs were tied together with a cord, and a sack was pulled over his head.

A shepherd’s son, Thomas Dytham, who was ten years old (born 4th April 1870), and lived at Great Woolstone, was going down to a field near the canal at about 8am. He saw a boatman dragging the body of a man partly out of the water. He could see that his legs were tied and a bag was over his head. Thomas saw the boatman pull the bag off, but he did not stop to see the body pulled on to the bank.

P.C. Lorton arrived after Birch had pulled John’s body onto the bank. They transported the body to the Swan Inn, Woughton, (now called Ye Olde Swan).

On Tuesday afternoon the inquest was held before J. Worley, Esquire, the coroner, and a ‘respectable jury’, of which William Higgins was foreman. John Birch was sworn in. He said that he lived at Stoke Prior, Worcestershire, and that he was a boatman. He said that John Twist had been employed by him regularly for about four months, and was paid per voyage, and that his pay was advanced as he required it, and he was supplied with food. He did not know whether John Twist was his true name, but he only knew him by that name. He estimated that John Twist was about 22 years of age. He know nothing of his friends, but believed he came from Birmingham.

Birch said he did not see Twist tying his legs, but he must have tied them himself, as nobody was with him. He said that Twist had never stayed behind before, but he didn’t think Twist was going away, because he didn’t have his coat or hat on, and had left some of his clothes on the boat. Both men said that John seemed fine, there was nothing strange in his conduct, and they did not suspect that he was thinking of committing suicide.

The next witness was George Massey, who was from Stoke Prior. He had known John since the beginning of the last winter. He said that he recognised the cord. It had been in the boat cabin before John got out of the boat, but he did not see John taking it. It must have been in his pocket, he added. Then George admitted that John had spoken to him about taking his own life on the previous Saturday, but George had thought he was joking. That Saturday night John had slept with his clothes on, but that was not unusual – he had done it on other occasions. He added that John used to drink heavily, but he had been teetotal on the last two voyages, and always seemed cheerful. He could think of no reason why John would want to kill himself.

The next witness was Thomas Dytham, who confirmed what he had seen.

The Coroner addressed the jury, saying that Thomas’s statement differed somewhat from the previous evidence, but it was clear that John Twist drowned himself, and it was for the jury to decide what state of mind he was in when he committed the act. This was because in those days suicide was a crime, and the only defence was temporary insanity.

The Jury returned a verdict of ‘Felo De Se’, a felony against himself. By saying that that he was guilty of taking his own life, he would forfeit his property to the crown, and woud be buried in shame. John’s body was duly buried without funeral rites later that evening. His death was registered in Newport Pagnell.

According to the press, there was a great deal of local gossip about the case. It was said that if the boatmen had returned to the spot sooner, John’s life might have been saved.

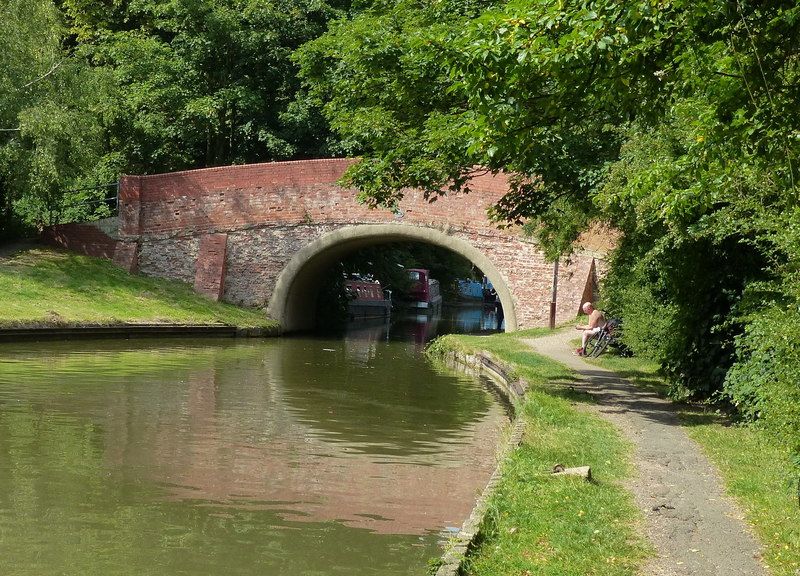

There are five bridges on the canal as it winds around Woughton on the Green. The photo shows the middle one, Peartree Bridge, which leads directly to the village. There is quite a bend in the canal here and it would not be possible to look back for long and see what happened. Did John Twist really commit suicide? Or did John Birch get off the boat, let his children carry on without him, and commit murder? Or was someone else involved? What do you think happened?

Sources: genealogical research, newspaper articles, mainly the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, and the Bucks Herald. The story was synicated and published in many other papers including Croydon’s Weekly Standard, Bicester Herald, London Daily News, Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette, Banbury Advertiser and others.

You can watch this story narrated on YouTube by ‘Yet Another Canal Adventure’ with my permission. Why not give them a like and a follow?